Israel and palestine

Israel and Palestine

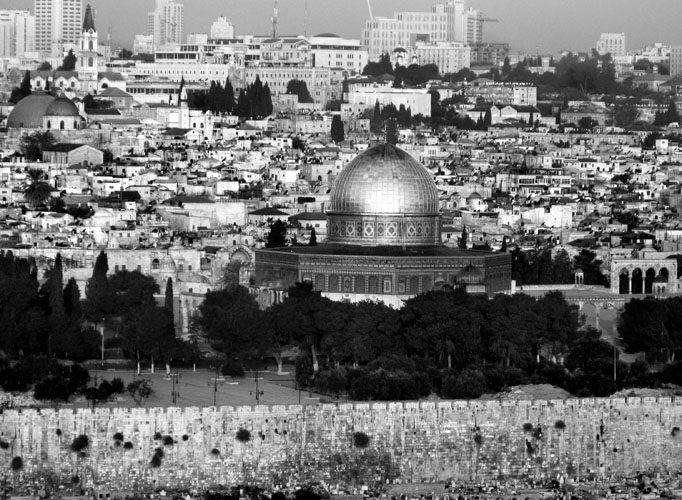

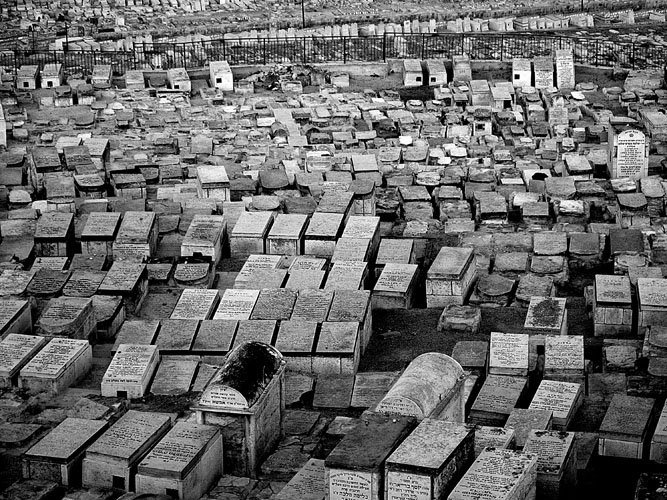

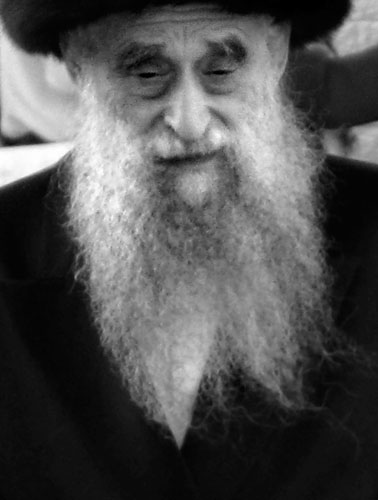

The critically complex issues dividing Israelis and Palestinians are difficult to understand, and nearly impossible to understand from a distance. Until you walk the streets of Jerusalem, or through the quarters of the Old City and talk to people, or just observe, does one begin to get a sense, or even a slight glimpse of what exists. An even sadder reality comes when one leaves Jerusalem to travel in and out of Palestine by crossing the many check points guarded by Israeli soldiers, many of them young teenagers.

There is a massive concrete wall surrounding Palestine that separates most of the West Bank from areas inside Israel. Now begin to only slightly comprehend the fear, hatred, and mistrust that dominates both sides.

The following article was written by Nigel Ashton for The Christian Science Monitor January 2009.

Nigel Ashton is a lecturer at the London School of Economics and the author of the biography, "King Hussein of Jordan: A Political Life." Mr. Ashton is the first person granted total access to the king's private papers, which included an archive of personal correspondence between him and every American president from Eisenhower to Clinton.

To find an answer that will not only halt the current violence but achieve a sustainable lasting solution, one should learn from the experience of one of the most critical players in Mideast peace throughout the latter half of the 20th century – King Hussein of Jordan.

Although the king died more than 10 years ago, he could still offer critical advice.

His private papers, sealed in the Royal Hashemite Archives until I was granted exclusive access in 2007, reveal a man inspired, frustrated, encouraged, and depressed by the strategies, engagement, and political vicissitudes of the relevant players. Hussein's private correspondence with every American president since Eisenhower offers new insight into what worked, what didn't, and how a revived effort to broker a lasting peace between Israel and the Palestinians might improve America's chances of success in the region.

Jimmy Carter, "thrilled" by assurances that tackling Middle East peace topped Obama's agenda, similarly buoyed Hussein's hopes that the Carter presidency might hail a new era for the region. Carter's early pursuit of a multilateral peace followed the approach favored by the king. But with the dramatic visit of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat to Jerusalem in November 1977, Carter's multilateral process was effectively derailed. In the end, the 1978 Camp David summit produced a bilateral Egyptian-Israeli peace deal but neglected the fate of the Palestinians. In the king's view, until their fate was resolved, there could be no peace. President Carter, Hussein believed, allowed himself to be tempted by the low hanging fruit – a bilateral deal – and abandoned his earlier aspirations for a regional peace deal. In a letter to Carter, the king explained his frustration on behalf of his fellow Arabs, writing, "[M]ost Arab parties, including Jordan, see the [Camp David] resolutions drawn up by the United States... as successfully achieving the well-known Israeli objective of isolating Egypt from the Arab camp and thus weakening it further."

Thirty years on, the Palestinian question remains unsolved. Hussein would probably urge the President of the United States to establish and maintain a dogged focus on a comprehensive, multilateral solution.

Like Obama today, President Reagan entered office with a large fund of goodwill among America's Arab allies. Yet early on, Reagan's failure to master even the basics raised serious doubts with the king.

By contrast, Hussein always knew where President George H.W. Bush stood. Despite deep disagreement with Bush over the Gulf War, the letters that flowed between them present a straightforward and respectful policy dialogue.

The channel allowed Hussein to express privately his "disillusionment and deep disappointment over the divide which seems to increasingly separate genuine Arab and Muslim aspirations and legitimate rights and United States policies towards us." For his part, President Bush's frustration with the king is evident: "Your words exculpate Saddam Hussein for the most serious and most brazen crime against the Arab nation by another Arab in modern times."

It was Hussein's involvement in the US-backed peace process after the Gulf crisis that formed the backdrop for the close relationship he developed with Bill Clinton. In contrast to Reagan, Clinton took time to study the substantial US military and economic aid package the king requested in June 1994 during the peace negotiations with Israel.

Clinton and Hussein shared a commitment to negotiating a comprehensive Middle East peace. After Hussein's death, the president wrote to his son King Abdullah commending Hussein's "dedication to peace and his commitment to the universal values of tolerance and mutual respect… He was an inspiration and model for us all."

A lesson here for Obama: Details impress.

If Obama wants to learn from his predecessors, understanding their relationship with King Hussein – his frustrating history with Carter's dashed effort, Reagan's lack of one, fundamental disagreements with Bush Sr., and a close but ultimately failed effort by Clinton – could give the new president the best chance at a meaningful, sustainable peace for the region and the world.